The comic book barcode is a funny thing. Some books have them and some don’t. Those that do can be confusing as they might have 13, 14, or 17 digits contained in them. In some cases you could even have two copies of the same issue which have entirely different barcodes on them. Oh the insanity!!! This article gives a very brief history of barcodes on comic books but is primarily on how to interpret the modern comic book barcode in use since 2008. Look for a more in-depth article on the history of comic book barcodes in the near future.

Why Barcodes at all?

Barcodes have been used in the United States since the early 70’s and quickly became a common practice that allowed for easier and more efficient tracking of sales and inventory for businesses in most retail industries. Newsstands and grocery stores were quick to adopt this new technology. At the time this is where nearly all comic books were purchased so publishers started using early UPC codes in the mid 70’s. With the rise of the independent comic book shop in the late 70’s publishers needed to know the difference between books sold to newsstands and to local retailers. These new local retailers weren’t as technologically savvy and publishers found it easiest to just remove the barcodes. But something funny happened. By the late 80’s the vast majority of comic books were being sold through local retailers. Comic books with barcodes essentially disappeared from the landscape.

As technology became less expensive more accessible, smaller retailers started benefitting from using barcode scanners to help manage their sales and inventory. As a response, by the mid 90’s barcodes started to reappear on comic books destined for local retailers, but these were oddly different from the ones still found on comic books at newsstands. There also wasn’t an agreed upon standard or requirement for including a comic book barcode and many retailers ended up frustrated by being unable to consistently scan barcodes to improve their businesses.

What was done about this?

Well into the 00’s retailers had frequent issues with scanning barcodes. In a early 2007 survey, Diamond Comic Distributors found that nearly 25% of retailers using a scanner system still had issues scanning barcodes. In 2007 Diamond responded by introducing a barcode standard to be used on the comics you buy in your local comic book shop. As of January 2008, all comics distributed through Diamond had to contain a barcode in a specified format. The format Diamond chose is what is known as the UPC-A Supplemental 5, or +5, format. This format was already being used by many of the major publishers but by making this the standard, smaller publishers could now have their sales and inventory tracked at retail. Retailers and publishers across the country rejoiced! (Not really, but that’s for a different discussion) The UPC-A +5 format looks like this:

What do all those numbers mean?

There’s actually quite a bit of information contained in those 17 digits. Here is the Anatomy of the Modern Comic Book Barcode and why this format is beneficial for publishers.

The barcode found on US published comic books distributed through Diamond actually comprises five different bits of information.

- The very first digit denotes a UPC approved number system. Comic book publishers will use 0, 1, 6, 7, 8, or 9, as certain numbers are reserved for specific uses. (e.g. 5 and 9 are used only for coupons, or 2 is used for random weight items like fresh vegetables.)

- The next five digits are the manufacturer code. Publishers are assigned this code by the UCC council.

- The next set of five digits are the product code and created by a publisher. Publishers will use a unique product code for each title they publish and will be used for all issues printed under that title. They need to buy the manufacturer and product codes. If you used the product code for each issue, that would get expensive.

- The final single digit is called the check digit and has to with math (I was told there would be no math). This digit is the answer to a math equation that the barcode reader calculates based on the first 11 digits of the UPC code. As long as the check digit matches the equation result the reader accepts the barcode as correct.

- Finally we have the 5 digit supplemental code found at the end. Assigning these do not cost the publisher anything so this is where comic book publishers provide information specific to the issue you are looking at. Publishers are free to use these five digits any way they wish, but again, Diamond requested a standardized format that works nearly all of the time. You’ll see how it breaks in extreme cases below.

How does this help me?

To see how this supplemental code can help you out, let’s dive into some examples of how the +5 code works and a couple of limitations. The +5 code contains three bits of issue specific information:

- The first three digits are the issue number.

- The fourth digit is the cover version.

- The fifth digit is the print run.

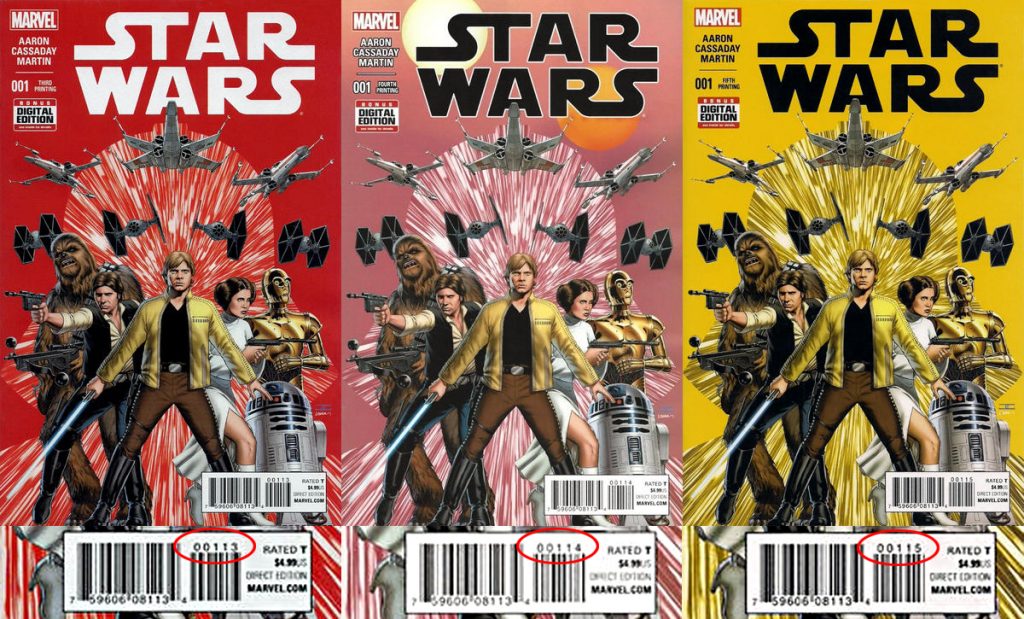

Basically, by looking at the +5 code you can see if the book you are looking at is a variant or secondary print run. Sometimes publishers don’t make those variations obvious so it helps that they specify this in the barcode. To help illustrate I’ve shown six issue #1 variants from the 2015 relaunch of Star Wars (three of which I own, three of which I don’t).

The actual UPC-A code for these books are all the same; 7 59606 08113 4, but the +5 code changes for each variant.

- Upper Left: 00111 for issue #1; cover #1; print run #1

- Upper Middle: 00131 for issue #1; cover #3; print run #1

- Upper Right: 00191 for issue #1; cover #9; print run #1

- Lower Left: 00113 for issue #1; cover #1; print run #3

- Lower Middle: 00114 for issue #1; cover #1; print run #4

- Lower Right: 00115 for issue #1; cover #1; print run #5

You mentioned limitations. Will those affect me?

Probably not. The +5 code basically allows for 9 additional variants and 9 additional print runs if you use 2 thru 0. Star Wars #1 though has upwards of 80 variants. Most of these have individual +5 codes but a few might not. So what did Marvel do? From what I can tell they just started using the last two digits together to denote the variant number. With 7 print runs of the first cover and approximately 70 other variants, Marvel should still have finished under the theoretical limit of 100 versions of a single issue. What DC did for Dark Knight III #1 and it’s supposed 100 variants I do not know. They printed the barcodes on the back so I can not see them in scans.

The other possible limitation is issue number. The +5 code essentially allows for up to issue #1000 by displaying 000. Issue #1001 would be shown as 001, the same as issue #1. Since the advent of the modern comic book barcode no title has printed 1000 issues so that hasn’t been tested yet. But we recently had an old, relatively unknown title hit issue #1000. You may have heard of it, Action Comics. You know, the one with the super swell guy who flies around in tights and a cape. Yup, DC is the first that I know of to have to reset the barcode odometer so to speak. Luckily, they didn’t start using the +5 format barcode until #693 in November 1993, and even that has a fortunate caveat as DC has changed the 5 digit product code a couple of times since.

What about those other barcodes you mentioned?

The previous barcode types used by the comic book industry, not to mention when they were used, if used at all, is a whole other can of worms. I’ll be tackling that subject in a future article. In the meantime, here is some bonus UPC info for you data nerds; manufacturer codes for some of the larger comic book publishers:

Marvel – 7 59606

DC – 7 61941

Image – 7 09853

Dark Horse – 7 61568

IDW – 8 27714

Dynamite – 7 25130

Titan – 0 74470

A final note: Trade Paperbacks and Graphic Novels

Trades and Graphic Novels are sold in bookstores so they have different standards they must follow in regards to barcodes.

- If they use a +5 format, the additional numbers typically indicate the book price. (Ex. 02499 would indicate a price of $24.99)

- As they are likely to have worldwide distribution it is not uncommon for them to use an EAN-13 format. This is very similar to the UPC-A but includes 13 instead of 12 digits.

- They will use an ISBN number which is a global standard for book publishing.

Hope this helps to demystify the modern comic book barcode. Thanks for reading!